The famous Mumbles Train en route to Oystermouth

Although these were turbulent times, there was little evidence of any concern being felt by these youngsters on this happy day. There was a sense of déjà vu, after all, the current German/Polish crisis was but one of a series and would probably just fizzle out, as had all the others.

We all know now that it was not to be like that. This time it did not “just fizzle out” and during this coming holiday, a cataclysm was triggered off which shook the very foundations of civilised life.

Previous crises had prodded Britain into preparatory action, signs of which were manifest in Mumbles but, now, there was a greater degree of urgency and action was being stepped up. The Royal Navy made its presence felt at Mumbles Head. The Army commandeered the Mumbles Hill, cocooned it with concertina barbed wire and posted armed sentries at all access points. The Royal Artillery moved in and with them came their 3.7 anti aircraft guns. A causeway was constructed from the lighthouse to the little beach by the Pier and provided access to the Outer Island for the installation and manning of coastal defence guns.

Khaki Battle Dress

The new khaki battle dress became an increasingly familiar sight in the village and more, and more, 3-tonner trucks groaned their ways through the Dunns to the Head, or to camps in Gower, packed with singing troops:

… “South of the Border, Down Mexico way…”

Fairwood, too, had shut its doors and the RAF undertook the massive task of creating a fighter station, with all that that entails. The blue uniform of the “Brylcreem Boys” now became a familiar sight in the pubs and shops and it was reassuring to see Hurricanes and the odd Spitfire, dressed for war, howling across the bay.

During the summer term, everyone of school age had been supplied with a gas mask and, now in the first week of August, it was the turn of the adults. Unpaid volunteers carried out size assessments (small, medium or large) on adults in the Church and Board Schools. A week later, the ARP proudly announced, in the Evening Post, that these same volunteers, using their own cars, had delivered gas masks to every adult in Mumbles.

The villagers carried on calmly, as usual, and although the main topic of conversation, was the threatening behaviour of Hitler, there was no sign of agitation. Mumbles people are not like that.

The summer of ’39 had got off to a wretched wet start, resulting in a back log of fixtures for most sporting clubs. Mumbles Cricket Club secretary; Bryn Critchett was in despair, faced with a nightmare August of three matches a week. Eric Stephens and Dick Stainton juggled the Tennis Club competitions and Coastguard, Mr. Chugg, prayed for divine intervention to sort out the Bowls tournaments. He must have been heard because, in the last week of July, the weather changed dramatically! Blue cloudless skies came to pass and Mumbles was blessed with sunshine, right through, to late September

Bank Holiday Saturday

At the crack of dawn on Bank Holiday Saturday, 5th August, organisers, Billy Howells, Jim Colley, Norman Jolliffe and Albert Williams, gazed anxiously skywards to check the weather. Preparations had long been made for the Mumbles Carnival and the British Legion Fete, but for success, fine weather was essential.

Fortune smiled upon them and, in glorious sunshine, the carnival, skilfully marshalled at Southend, wended its way through the village, en route to the Castle Field. What a carnival! To the pulse quickening beat of the gazoos, bass and kettle drums of six jazz bands, float after float glided by, bearing beauty queens, hospital tableaux, raucous pub groups and Buster David’s colourful “Buccaneers”. This latter float brought wistful smiles to old gents’ faces as grass skirted native beauties swayed to Buster’s Hawaiian guitar.

Amongst the colourful walking escorts was perennial favourite, “the absent–minded professor” (no trousers). Hitler and Mussolini goose-stepped by, Popeye handed out spinach and this year, for the first time, little Bryn Colley, dressed as a village curate, was alone. His big brother, Norman was at a TA Camp.

Cwmbwrla Comedy Band

No Mumbles Carnival was complete without our noble Lifeboat Crew who, sportingly paraded, fully equipped in oilskin rig and lifebelts, streaming with perspiration. That hilarious bunch of idiots who made up the Cwmbwrla Comedy Band brought up the carnival in the rear. This was a motley crew led by a tall, erect man dressed as a Scot. In front of his ankle-length kilt dangled a large whitewash brush. (Six months later, I saw this same gentleman in a different role. He was immaculately clad in Welsh Guards uniform, with puttees and gleaming boots. On his arms were the chevrons of a Colour Sergeant).

The Castle Field was packed to capacity with villagers of all ages. There was laughter, shouts and all those noises that blend together to make an indescribable mix – the sound of happiness! The crack of wooden balls against “glued-in” coconuts competed with Jim Colley’s raucous bellow, “Come and win a fortune! Buy a straw and match its number to my board!” Bells rang from roundabouts, the rolling horse threw its young riders, magnets picked up cardboard fish and Madame Rosa Petulengro told fortunes! Everything was buzzing!

As trophies were awarded for the winning costumes, so the first runners in the Evening Post, Swansea/Mumbles Road Race began to arrive. All were local amateurs who had trained assiduously (some for as long as a week) on chips, Woodbines and draught beer. Red faced and nearing collapse, they lurched into the arena like zombies. The winner (after treatment) was awarded the Evening Post cup, by the Town Mayor.

The highlight of the day was the jazz band competition. We marvelled and we clapped at the precision marching. Each band of forty men had drilled for many months and competed in fetes all over the country,’ bussing in from afar for this event.

Fairy Lights

Celebrations went on into the evening and as the red sun began to sink behind the castle, fairy lights lit up about the arena. Jim Kostromin, over his sound system, invited the first dancers to step out to Roy Fox’s haunting, “Whispering”. It was dance time and a delightful way of bringing the day to a close. The 1939 Fete had been a very special one for all of us (even more so, in retrospect).

All over Britain, on this lovely Bank Holiday Saturday, similar events had been enjoyed. This was our way of bonding and was in extreme contrast to the soulless Nuremberg rallies in Nazi Germany where bonding was fostered by the mass hysteria of jack-booted thousands, chanting their “Sieg Heils”!

Mid-August

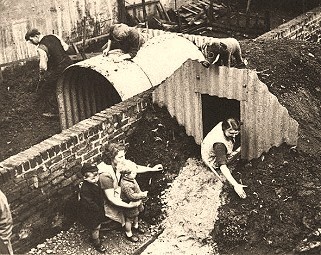

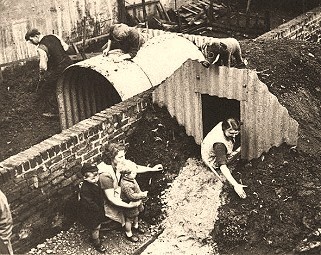

By mid-August, packages of angled steel bars, nuts and bolts and curved corrugated sheeting, appeared on doorsteps. The Anderson air raid shelters had arrived! All over Mumbles, grumbling fathers, helped by reluctant sons, were seen digging pits in gardens, to accommodate the steel bases of these shelters.

It was my pleasure to help Donald McGuffer to erect his in the front garden of his tiny home in Albert Place. Sadly, genial Donald was killed in action in North Africa a few years later.

For some families the impact of war came early. Barbara Smale came home from Sunday School to see her three TA brothers frantically, polishing brasses, blanching webbing and cleaning boots. All three had been called to the Colours and were to report to the Drill Hall immediately. It is not hard to imagine the effect this had on a 14-year-old girl! By the Grace of God, all three survived a long war and came home.

Barbara’s future husband, Colin Venn, was suddenly uprooted from Newton, to live in Langland. His father was the Head Groundsman at the Langland Bay Golf Club. The entire ground staff was called up. Mr Venn, as a result, found himself in sole charge of everything and had to move in! Not only was he now the Club Steward but, also, had to accept having sheep to graze upon the course. He was now a shepherd. Young Colin was a Sea Cadet and, like all his contemporaries, anxious to enlist. His wishes were granted and in 1943, at the age of seventeen and a half, he enlisted in the Royal Navy to see action in places he had never heard of.

With the sun shining at last, Campbell’s paddle steamers did a tremendous business, sailing up, down, and across the Channel. An adult day return to Ilfracombe cost 4s.0d. and all boats could be boarded from the Mumbles Pier. So convenient!

War preparations continued. The British Legion Hall, (then on Station Square behind Boots), had part of the premises requisitioned to establish the Mumbles First Aid Post. Amazonian ladies, under the direction of the formidable Mrs. Kostromin, hovered outside, so impatient for action. Loudly protesting, struggling kids were dragged in for bandaging and splinting practice. Many never recovered.

Marine Villa ~ ARP HQ

Marine Villa, Newton Road was set up as the ARP. HQ. Warden training had been going on for over a year. A Mumbles man, Haydn Hughes, of Caswell Road, was appointed to the very senior position of Divisional ARP Warden for No.2 District. Haydn Hughes was later, and justly, honoured for his superlative work during the Swansea Blitzes. ARP volunteers were unpaid but there were perks for joining, such as the provision of a steel helmet, a far superior gas mask and an impressive silver badge.

A mysterious cylindrical object materialised upon the top of a lamp standard opposite the Marine Hotel, in Southend, and policeman, Ted Southall, informed us that it was an air raid siren. Another one appeared, simultaneously, in Newton.

'Down the front'

With temperatures in the high seventies, we swam every day, “down the front” and in Little Langland. The dustmen came daily to collect the refuse. The postman delivered the mail four times a day and Queen Victoria’s penny post still cost just that.

Johnny Davies’ chip shop was at its apogee, his little shop in Chapel Street was, indeed, “….the plaice that launched a thousand chips.” 3d bought a cutlet of hake plus chips, cooked in flavour-enhancing, high cholesterol animal fat. This was the apotheosis of culinary élan and worth dying young for. On Saturdays, on Johnnie’s doorstep, an old lady in Welsh costume would materialise out of thin air, with a tub of Penclawdd cockles, sold by the half pint. She never spoke. Nobody ever saw her come or go.

Smith's Crisps 2d. a packet

Glyn Maggs, behind the bar of the Vic’ served, Hancock’s Dark Malt at 6d a pint, Smith’s Crisps 2d a packet, Players’ Medium Cut cigarettes at 6d for ten and five Woodbines for 2d. A full bottle of Haig’s Scotch Whisky was 12s.6d and a tot across the counter, cost 3d. Prices unchanged since WW1!

Glyn Maggs, behind the bar of the Vic’ served, Hancock’s Dark Malt at 6d a pint, Smith’s Crisps 2d a packet, Players’ Medium Cut cigarettes at 6d for ten and five Woodbines for 2d. A full bottle of Haig’s Scotch Whisky was 12s.6d and a tot across the counter, cost 3d. Prices unchanged since WW1!

Mary Taylor’s sweet shop on the corner of John Street sold a 2oz bar of Cadbury’s for tuppence and one penny bought 2oz of any sweets from the open trays in her little shop window.(no charge for dead flies).

On the beach at Langland, Mr. Edwards’ Café was enjoying a bumper summer. Set teas, at 9d and 1s 0d, attracted queues and, for a deposit of 1s.0d, customers were allowed to take tea on the beach, set up on tin trays. Edwin Timothy, leased out Corporation deck chairs at 3d a ticket (2d refundable upon return of the chair) whilst his colleague, Barney Davies, kept a watchful eye on suntouched bathers cavorting in the surf. The privileged beach tent owners supped tea, purring with contentment on their elevated decking, well away from the masses. And Europe seemed a long way off.

Continued on page two

Glyn Maggs, behind the bar of the Vic’ served, Hancock’s Dark Malt at 6d a pint, Smith’s Crisps 2d a packet, Players’ Medium Cut cigarettes at 6d for ten and five Woodbines for 2d. A full bottle of Haig’s Scotch Whisky was 12s.6d and a tot across the counter, cost 3d. Prices unchanged since WW1!

Glyn Maggs, behind the bar of the Vic’ served, Hancock’s Dark Malt at 6d a pint, Smith’s Crisps 2d a packet, Players’ Medium Cut cigarettes at 6d for ten and five Woodbines for 2d. A full bottle of Haig’s Scotch Whisky was 12s.6d and a tot across the counter, cost 3d. Prices unchanged since WW1!