The Bells of Santiago

In 2010 Oystermouth PCC made the decision to gift three historic Spanish bells to the people of Chile. The 'Bells of Santiago' had been housed in the tower at All Saints' from the late 1860s. They were among the only objects to survive a devastating fire at the Jesuit Church in Santiago on 8th December 1863

The fire claimed the lives of over 2,500 people, mostly women and children, and is thought to be the worst fire disaster in recorded history.

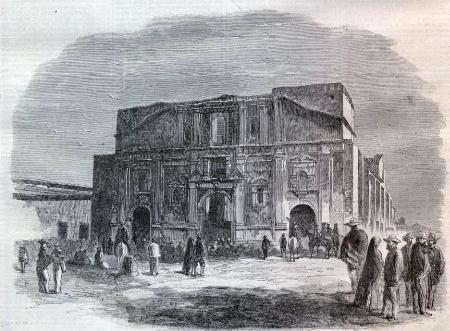

The bells are thought to have been made in Huesca, in North Eastern Spain, and date from 1753 to 1818. They were taken to the large 'Church of the Company' by Jesuits, some time during the middle of the 19th century.

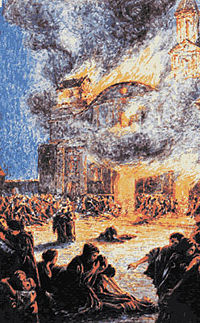

What happened? It was the evening of 8th December 1863 at Santiago. A great religious service was underway with over 3,000 people present. The New York Times reported that it was a great triumph for the Clergy that so many attended. But the celebrations turned to tragedy. More than 2,000 people ( some reports claim 2,500) mainly woman, perished by fire. Bystanders were powerless to help, so intense were the flames.

The three large bells that were on display in the porch at All Saints Church are of Spanish origin and date from as early as 1753. It is likely that they were cast in Spain and shipped to Chile. They are inscribed in Latin and in Spanish. The bells were presented to All Saints, in exchange for the medieval bells, by Graham Vivian of Clyne Castle whose family had many business connections in the copper ore trade in South America.

The original intention was that the Spanish bells were to be broken up - but they were presented instead to All Saints. Graham Vivian is on record as having stated that he was unaware which Santiago they came from. However the belief that these Spanish bells came from Sanitiago in Chile has been held for a very long time.

Here is the story of 1863 disaster

After the fire tragedy of 1863 when the Jesuit Church de la Campana was razed to the ground in Santiago, the bells were sold for scrap and shipped to Swansea, blackened with smoke and installed in the Norman tower of All Saints. This was a decision of the Vivian family of Clyne Castle Swansea - who had business connections with the copper mines in Chile. In 1964 the bells were taken down from the tower as it could no longer support their weight.

The date was the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of Mary in the Roman Catholic calendar. There was a month long Festival leading up to this day celebrated with orchestral music, singing and an astonishing profusion of incense, oil lights, liquid gas lights, wax candles which glittered and flared in every part of the Church. The cult of the veneration of Mary was particularly strong in this church

Each evening during the month, the Church shone with a sea of flames and fluttered with clouds of muslin and gauze draperies. It was reported that 20,000 lights shone that fateful evening. They could only light up everything by starting in the afternoon and the work of extinguishing was only ended late into the night. Here is an image from Harpers Weekly dated 1864.

8th December was a great feast day and in 1863 the Church was prepared as usual. The Church could hold almost three thousand souls. It possessed a spacious nave where the people would assemble. There was only one principal door. Many who had visited the Church in the past had complained of the suffocation caused by the smoke, the candles and danger of so many lights. But no measures were taken to prevent a serious accident.

At 6 pm the doors of the Church were opened and around 3,000 women and a few hundred men took their places. It was crammed to overflowing. It was the 'Month of Mary' and no one could bear to miss the closing sermon of Urgate the Jesuit priest.

The servant boys, or lamplighters, commenced lighting the lamps which were fuelled with hydrogen gas, or parafin or oil. The principal image of Mary was supported by a fine crescent of brilliant lamps in the centre of the High Altar.

An accident happened a few minutes before 7pm. A gas lamp at the top of the High Altar ingited some of the veils that adorned the walls. The High Altar was set on fire. The fire soon spread in under two minutes. The advance of the fire was more rapid than the panic of the congregation and soon the wooden roof and dome were ablaze. There was great confusion as all rushed the central doors. About a third of the congregation made their escape but contemporary reports tell of a great wedge of people locked in rows one upon the other and no one could move. Those inside died from the flames and the smoke. the big hoop skirts worn at the time made escape even more difficult. It was said that all the priests escaped unharmed (New York Times - see link below)

There is a report of a man who tied a rope to his horse and threw the other end of the rope into the mass of the people. Soon there was silence from the people, the screaming had all stopped, the Church was now a furnace. Suddenly the central dome crashed in the middle and with it the spire.

Later that evening the fire burned itself out. The bodies of the dead lay in horizontal strata or in groups as the fire had caught them The greater portion was near the doors, others under the great bells which had fallen on a group nearest the principal door. Entire families were lost. It took more than ten days to recover all the bodies , most of which were beyond recognition. They were placed in a mass grave at the Cementerio General de Santiago. The remaining walls of the Church were torn down and a garden planted. This was one of the worst fire tragedies ever. Here are some contemporary images:

Nothing now remains at the site of the tragedy, except for the garden and the mysterious and unique Ombu tree, a massive evergreen herb native to South America that spreads to 40ft wide (12-15metres) and upto 60 feet tall ( 12 - 18 meters). Its sap is poisonous.

|